1. Introduction

TypeScript is not real when compared to the type systems found in languages like C# / Java for example, it has absolutely no power at runtime because it does not exist in the native code we send to the browser, so we must not write development code that skews logical inference as that will reduce safety.

This document aims to define guidelines that will help us work better with TypeScript therefore increasing the robustness of our code.

2. Avoid defining domain “source of truth” in the FE code

If possible we should avoid manually defining types in the front end code for anything that falls under domain – like business rules or entity specification.

For example using query/ mutation types from your GraphQL schema for a form type instead of defining our own separate structure that needs converting before submission (mutating).

Another example could be using a query type like:

|

1 2 |

type Address = CustomerQueryQuery$data['address'] type Props = { address: Address } |

Note: This may not be possible in certain legacy code, so this guideline is mostly aimed at the more modern parts of the code base.

3. Avoid using the any type

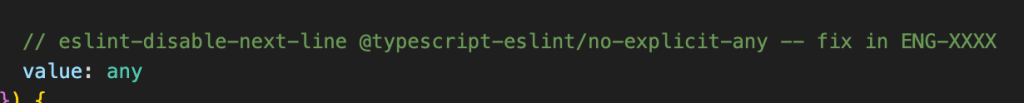

We should not use explicit any types in our code unless absolutely unavoidable. any is no better than using dynamic vanilla JS. For times when we need to use it we can suppress with a description:

3.1. Consider using the unknown type Documentation – TypeScript 3.0

The unknown type is much more robust and valuable when compared to any mainly because of this point:

“no operations are permitted on an unknown without first asserting or narrowing to a more specific type“

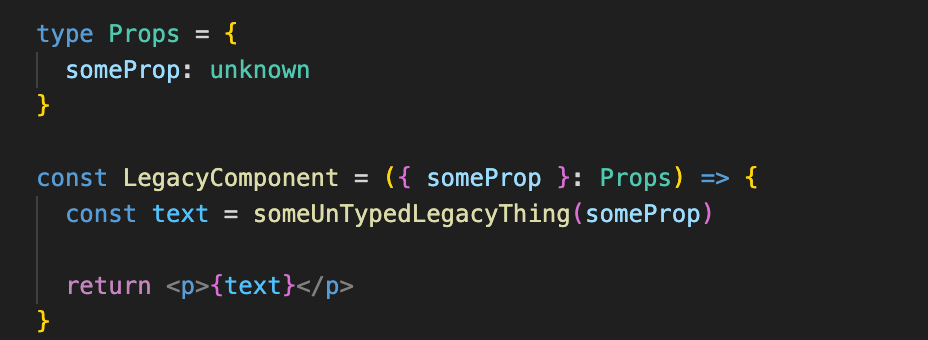

In a nutshell – you can use unknown instead of any if no specification is required, take this example:

unknown was sufficient here because no specification of someProp was ever required in the code.

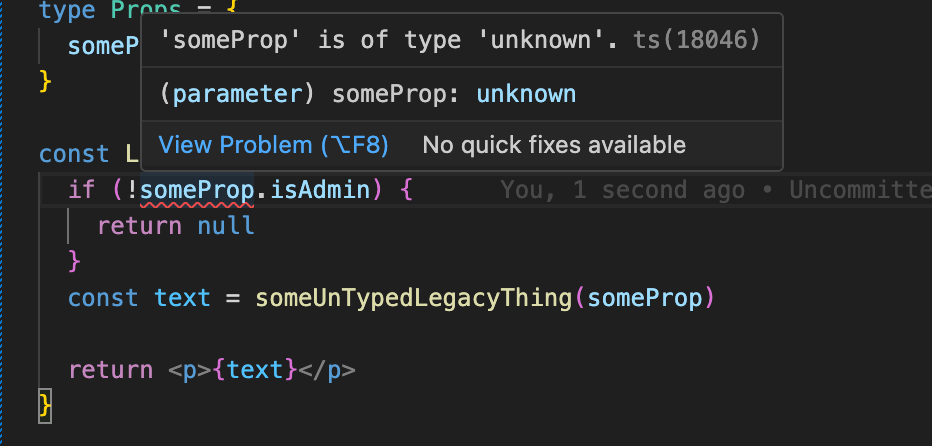

Now let’s now see the power of unknown compared to any. Say if we wanted to extend the code here to evaluate something based on someProp:

Because we used unknown we now get an error in our code and to fix this we must provide more specification. If we had use any type here there would have been no error and that would greatly reduce the robustness of this code.

3.2. Gather specification based on what exists in the code “today”

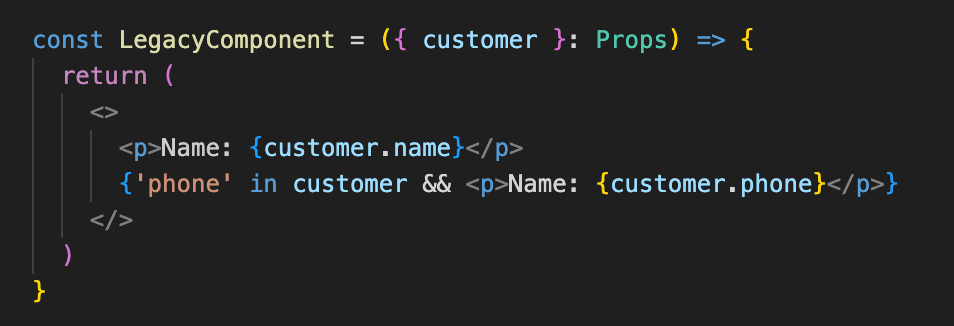

TypeScript is just development code so adding/ changing a type for something can’t break anything in production. So let’s say I find this legacy component:

It is a really quick win to “lock down” this component with some specification that can better protect it from regressions until we migrate from legacy. We can easily infer from the code that today this component works based on a source of truth equal to:

You can also consider debugging the runtime or looking at rest network requests to get the real shape of variables at runtime.

4. Preserve real time inference using satisfies operator

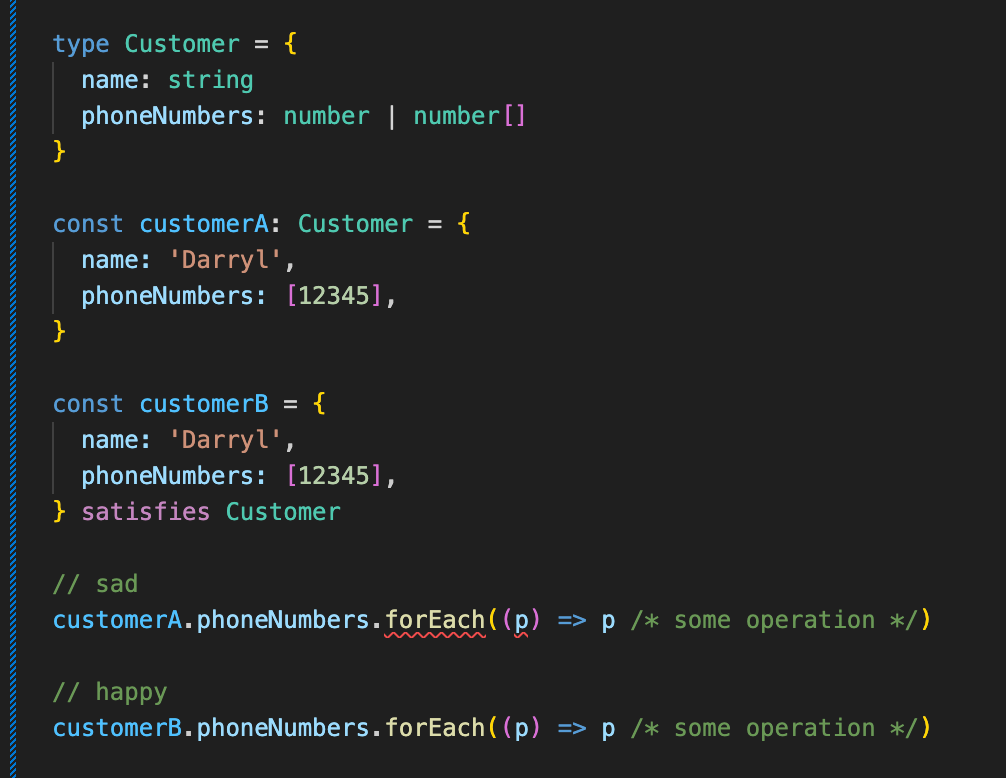

We can give ourselves more logical freedom when working with types if we allow the real time inference to be persisted with each line of our code, sometimes this can get lost if we use explicit type annotation. Let’s look at an example:

We can see that the Customer type accepts either a single number or array of numbers for phoneNumbers property. And we can also see that both our customers match the latter of using an array. In that case both should be able to call the forEach extension method…..but based on TypeScript’s current (mis)understandings customerA does not safely support this.

That is because when we use type annotation the inference is based on the original broad type for Customer and not the actual shape of the object that used it. This is when satisfies helps us because it can enforce correct constraint but also allow us to base the inference on the real object, which allows TypeScript to determine that forEach is safe for customerB

5. Prefer explicit type annotation over casting

We should always first try to annotate the type directly instead of casting like:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

// plan A const variable: SomeType = { ... } // plan B const variable = { ... } as SomeType |

5.1. Why is casting worse?

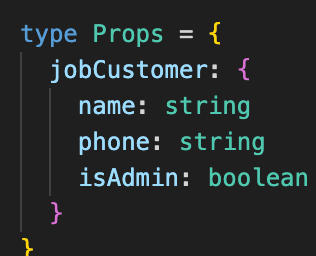

When you annotate the type directly TypeScript will check for guaranteed commonality in specification which provides the most safety, but when we cast we are only asking TypeScript to check for possible commonality, for example consider these types:

|

1 2 3 4 |

type CustomerTypeA = { name: string phone: number } type CustomerTypeB = { name: string } type CustomerUnionType = CustomerTypeA | CustomerTypeB type Props = { customer: CustomerUnionType } |

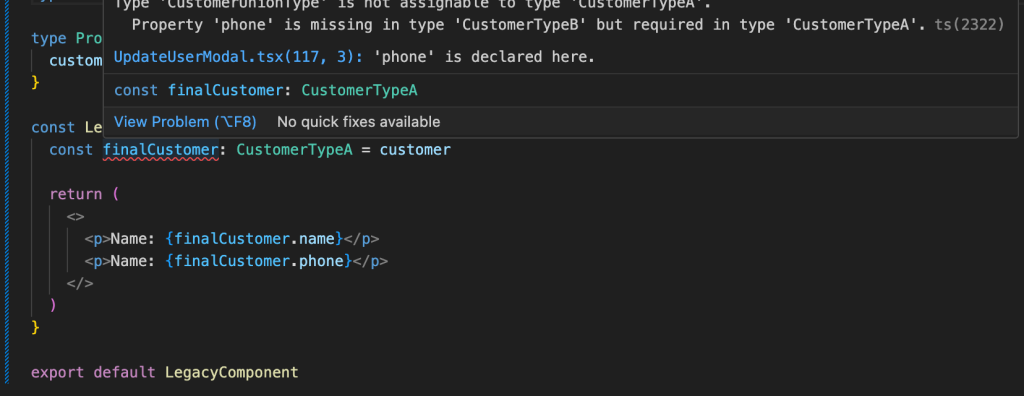

We are saying that we expect two possible specifications for Customer but we don’t know for sure which….let’s look at why casting can be dangerous:

Notice how there are no errors even though it is not guaranteed that phone exists. Let’s see why explicit annotation is better:

TypeScript was now forced to evaluate if this was guaranteed vs just being a possibility….and in this case it was not guaranteed.

How could we solve this? We can write runtime checks to guard against using the wrong scenario:

TypeScript is now happy because it already knows this is a possibility based on the union type and before executing anything at runtime we actually checked if the key exists.

5.2. Never use the double cast mechanic

In TypeScript it is possible to force a type like:

|

1 |

const variable = { ... } as unknown as NonsenseType |

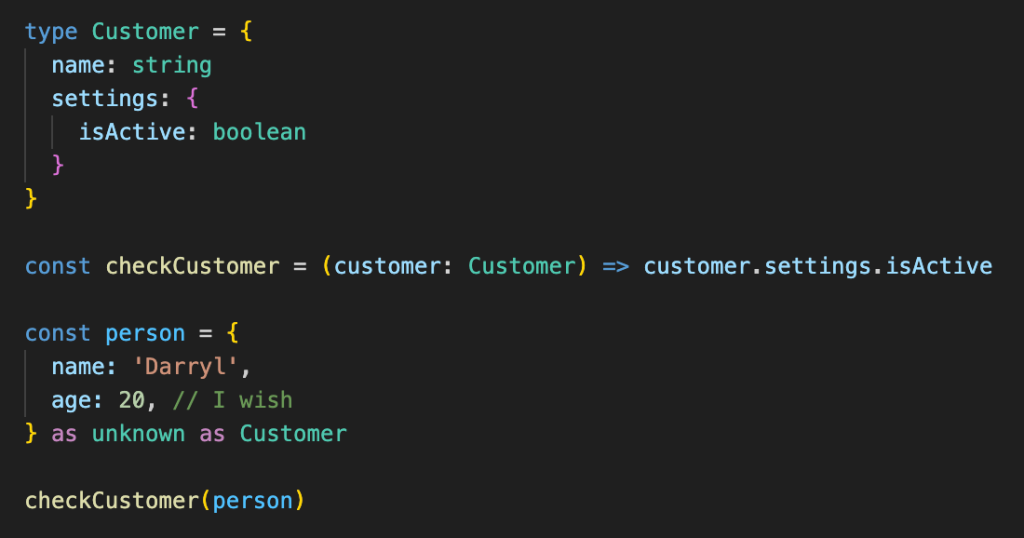

Let’s look at how incredibly dangerous this is:

This call of checkCustomer will error at runtime when it tries to access the nested property because we forced TypeScript into accepting that the person object met the specification of a Customer even though it is clear to see that it absolutely did not, when we do this all logical inference is cancelled out and this is very dangerous.

5.3. If you must cast – don’t cast too soon

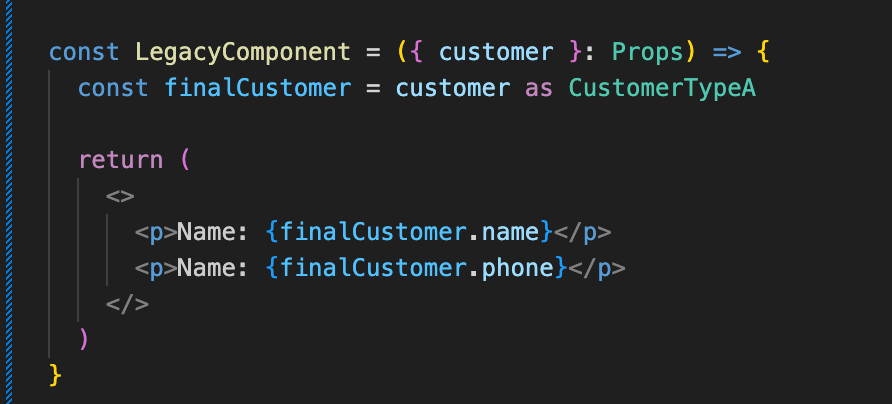

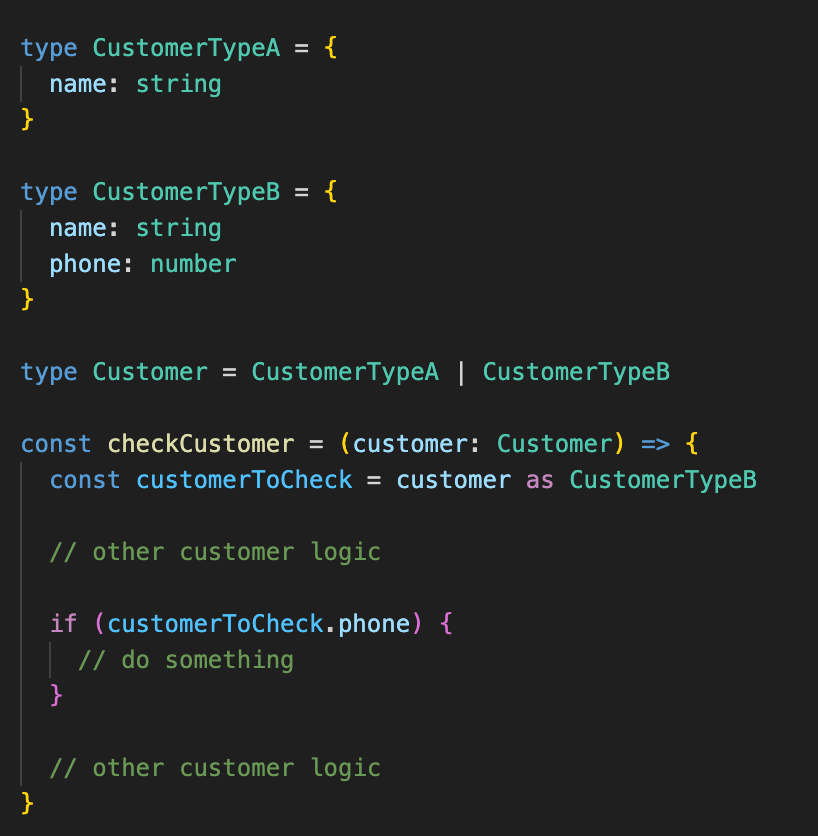

As mentioned before we should try to find ways to write our types without needing to cast, but let’s pretend it cannot be avoided in this scenario and in that case we can at least ensure that we cast just in time. Let’s consider this code:

You can see that we immediately told TypeScript to treat customer as the possible type of CustomerTypeB which means that all code in this branch will be evaluated with that specification.

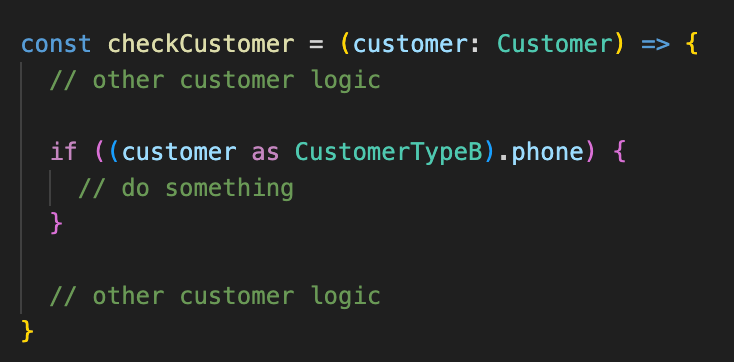

What we should do instead is wait until the last point at which we need to consider if something from that possible type might be the case, this looks like:

You can see that we only applied the cast just in time, and this way it has no impact on evaluating other logic in this function.

6. Improve specification with discrimination types

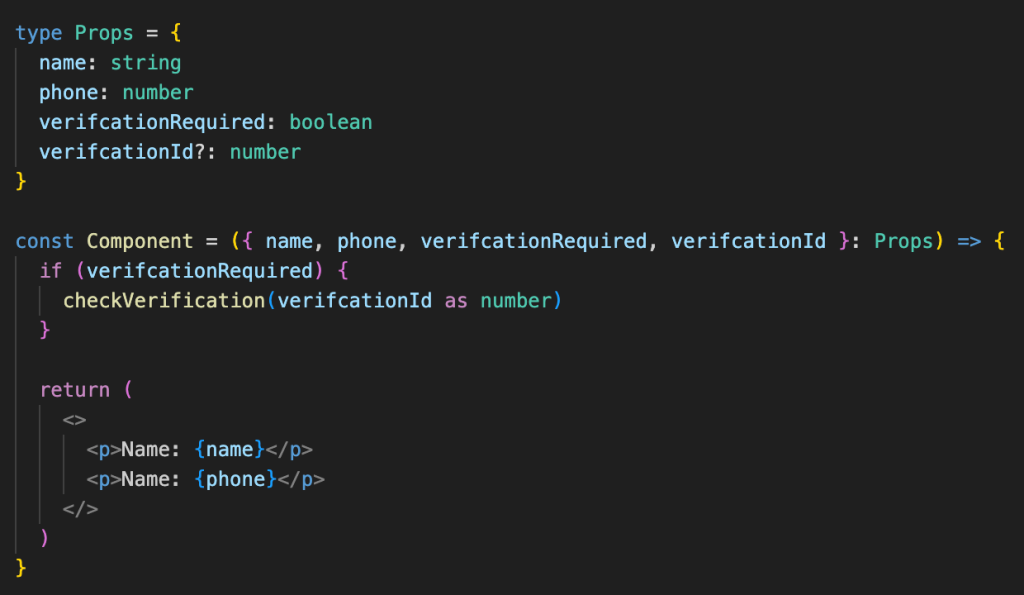

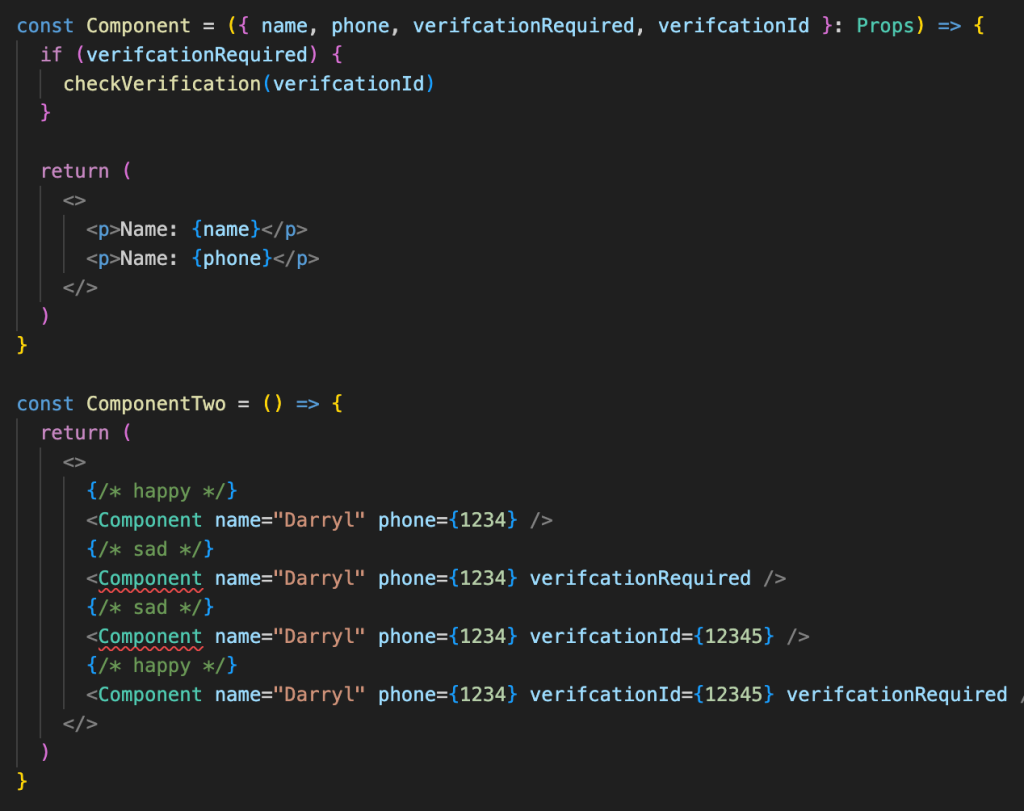

Let’s consider this component:

If we look at this from a high level we are saying that we can have:

- a customer with a

name,phoneand requires no verification - a customer with a

name,phone, requires verification and should have averificationId

The problem is that by using a single broad type we are not “discriminating” between these two scenarios, one clue to this is the fact that we had to cast when passing the verifcationCode to checkVerifcation when really we should only be calling that with an actual code when the scenario calls for it.

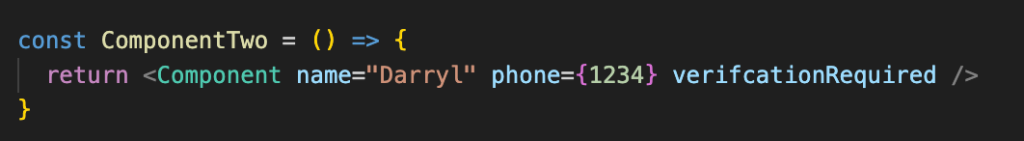

We can also see the problem manifest in a consumer of this component, for example:

Notice that there is nothing telling us that I did not provide verificationId even though we specified that verification was required.

How can we fix this? Let’s restructure our props to use a discrimination type:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

type PropsWithOutVerification = { name: string phone: number verifcationRequired?: never verifcationId?: never } type PropsWithVerification = { name: string phone: number verifcationRequired: true verifcationId: number } type Props = PropsWithOutVerification | PropsWithVerification |

and let’s take a look at our components/ consumer again with the new types applied:

Noticed that we no longer need to cast in the component itself when calling checkVerification because TypeScript was able to infer that: if verifcationRequired is true then a verificationId must have been supplied.

Also noticed that our consumers now complain if we don’t call the component in a way that makes sense based on the different scenarios defined by the discrimination types.

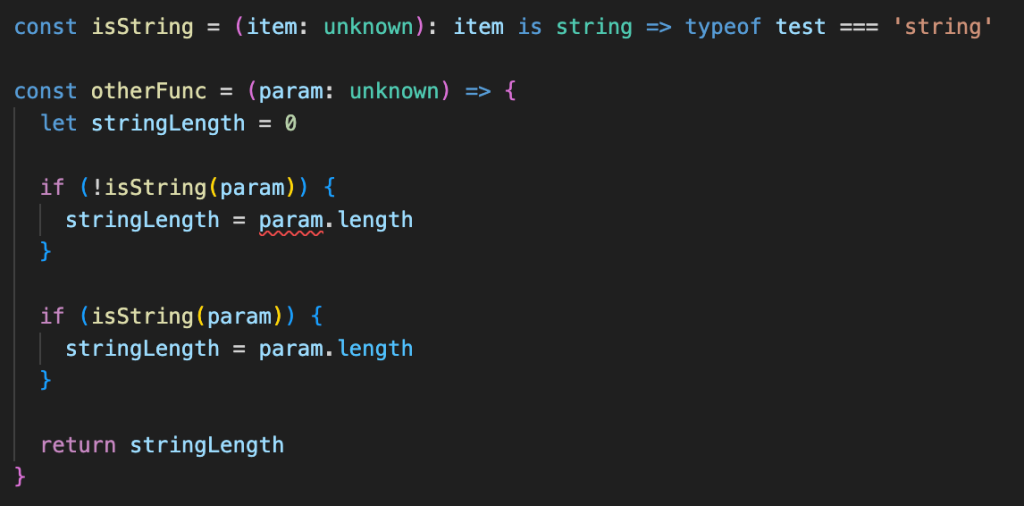

7. Avoid using the is keyword

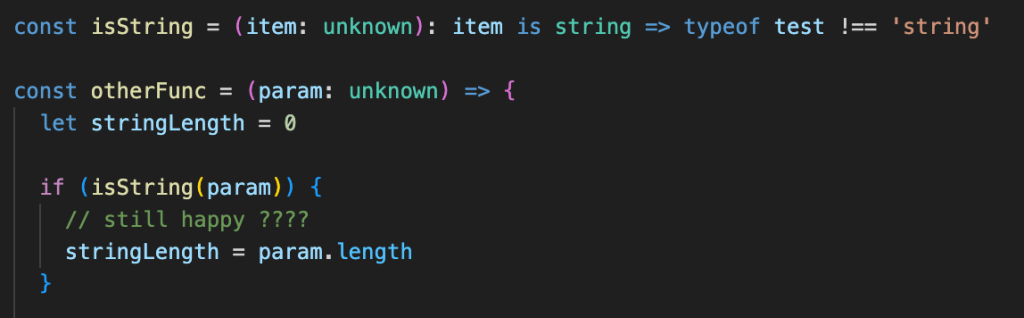

is is very brittle because it leans too heavily on forced assertion of specification rather than logical inference. Let’s look at this example:

This code is currently safe because the isString function only returns true if typeof test === 'string' which means that asserting item is string in that case is correct.

But what if we accidentally inverted the isString to typeof test !== 'string' and check the code again:

You can see that the is keyword is too open to error because the checks that justify the type assertion don’t actually have to make sense.

8. When suppressing prefer ts-expect-error over ts-ignore

Simply put ts-ignore will completely switch off TypeScript evaluation for that piece of code, so we would never know if other issues crept in, or when the error has been resolved i.e. the suppression no longer needed).

ts-expect-error on the other hand will still evaluate the piece of code but simply not present the error as a problem, that way it will be able to determine when the suppression is no longer needed and flag it.

In conclusion – we should not use ts-ignore unless unavoidable and in those cases provide rationale.